The nursing associate role is new and it is important to understand support needs and career aspirations of trainees. This article comes with a handout for a journal club discussion

Abstract

The nursing associate role was introduced in England to bridge a skills gap between healthcare assistants and registered nurses, and to provide an alternative route into registered nursing. Previous research has highlighted challenges that trainee nursing associates face and how qualified nursing associates are being embedded in the workforce, but no studies have explored trainee experiences over time. We conducted two surveys about support experiences and career plans over a one-year period: there was an increase in support from clinical supervisors and nursing associates, and a reduction in support from academic tutors. Support in the clinical setting improved from 56% to 65%. Only around 10% intended to remain in a nursing associate role and more than a third were uncertain about progressing to registered nursing. Most wanted to remain in their current organisation but a third were looking to change clinical setting. Understanding these patterns will help align individual career planning with organisational workforce requirements.

Citation: Robertson S et al (2021) Support and career aspirations among trainee nursing associates: a longitudinal cohort study. Nursing Times [online]; 117: 12, 18-22.

Authors: Steve Robertson is research programme director; Rachel King, Beth Taylor and Michaela Senek are research associates; Sally Snowdon is university teacher; Emily Wood is research fellow; Angela Tod is professor of older people and care; Tony Ryan is professor of older people, care and the family; all at the Division of Nursing and Midwifery, University of Sheffield. Sara Laker is associate professor, Winona State University, Minnesota, United States.

- This article has been double-blind peer reviewed

- Scroll down to read the article or download a print-friendly PDF here (if the PDF fails to fully download please try again using a different browser)

- Download the Nursing Times Journal Club handout here to distribute with the article before your journal club meeting

Introduction

The global and local shortage of nurses is having a considerable impact on healthcare services (Marc et al, 2019). In the UK, shortages of nursing staff have been recognised as a significant threat to healthcare delivery (The King’s Fund, 2018), and these issues have been exacerbated by the Covid-19 pandemic (Anderson et al, 2021).

Background

In England, a review of nurse education and training (Health Education England, 2015) led to a proposal to introduce a new role – that of nursing associate – to:

- Bridge the identified skills gap between unregulated healthcare assistants (HCAs) and registered nurses (RNs);

- Increase routes into nursing.

After consultation and debate in the nursing profession, nursing associates became regulated by the Nursing and Midwifery Council (NMC); as such, they are subject to the standards required for entry and ongoing registration (Glasper, 2018). These standards set out the knowledge and skills required for safe, effective nursing associate practice (NMC, 2018). Training has to ensure:

- Exposure to all four fields of nursing practice (adult, mental health, learning disability, children’s);

- Experience in developing the skills needed to care for people in hospital, close to home and at home.

An assumption was made that around half of these nursing associates would progress to become RNs (Council of Deans of Health, 2017). In January 2019, after initial piloting and expansion of nursing associate training, qualified nursing associates began to be registered with the NMC. They are now becoming an established part of the health and social care system in England.

Research has begun to report on the motivations, experiences and aspirations of trainee nursing associates, and on the implications of embedding newly qualified nursing associates into healthcare settings. Vanson and Bidey’s (2019) evaluation of the trainee nursing associate programme, commissioned by Health Education England (HEE), suggests that trainees applied to the programme to develop their skills and progress their careers; for some, this included moving into RN training.

This national HEE evaluation also found challenges for trainees in both the academic setting (mainly linked to low confidence) and in clinical settings (a lack of understanding and acceptance by colleagues, and difficulties getting protected learning time). However, it also noted trainees’ enthusiasm and commitment, along with their high levels of satisfaction with the quality of teaching and support from their higher education (HE) institutions.

These findings align with those of Coghill (2018a; 2018b), who completed surveys and focus groups with trainee nursing associates in the North East of England, and King et al (2020), who undertook focus groups with trainees in the North of England. Both studies highlighted:

- Similar motivations around skill enhancement, career progression and stepping into RN training;

- Struggling with academic work;

- Lack of protected learning time;

- That support from peer trainee nursing associates was particularly important;

- That support from mentors and in clinical settings was variable.

King et al (2020) identified the importance of broader support networks that include line managers, staff in clinical placement areas and academic tutors.

More recently, as trainee nursing associates qualify and enter the workplace, research that focuses on this new role from a range of stakeholder perspectives has emerged. The National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Policy Research Programme has funded a large study looking at the introduction of the nursing associate role. An interim report, incorporating data from interviews with experts and a survey of chief nurses in England, has been produced by Kessler et al (2020).

Lucas et al (2021) completed interviews and focus groups with a range of healthcare stakeholders to explore their experiences of the newly implemented role. They highlighted how the role was adaptable to different clinical settings and provided a positive career development mechanism, but implementation was often restricted by the lack of clear communication and planning.

King et al’s (2021) cross-sectional survey of trainee and qualified nursing associates from across England identified concerns about the under- and overutilisation of their role, safety, staffing levels and missed care during the first wave of Covid-19 in England. Participants expressed pride in both maintaining high standards of care and enhanced teamwork during this difficult time. However, as yet, there is limited research that reports on how experiences and career plans might change for trainee or qualified nursing associates over time, especially when training during the pandemic.

Aim

This study aimed to identify how support experiences and career plans are reported by a research cohort of trainee nursing associates over a one-year period.

Method

We designed a longitudinal study that collected survey data from a research cohort of trainee and newly qualified nursing associates at two time points approximately one year apart. This forms part of a larger programme of research with trainee nursing associates that will also include qualitative data collection and work with stakeholders.

Trainees were invited to participate via email lists covering seven universities across England, and recruited between 1 April and 30 November 2019. Advertisements were also placed on Twitter. To obtain a range of responses, no restrictions were placed on the nursing fields that participants were from, or their stage in the training programme.

Participants were surveyed at two time points: 1 April-30 November 2019 and 20 July-12 September 2020. The survey began with questions relating to regional location, gender, age, ethnic background, and training or qualification status. Further survey questions were developed based on the research from Coghill (2018a; 2018b), Vanson and Beckett (2018), Davey (2019) and an exploratory focus group reported by King et al (2020); these are shown in Table 1.

Results

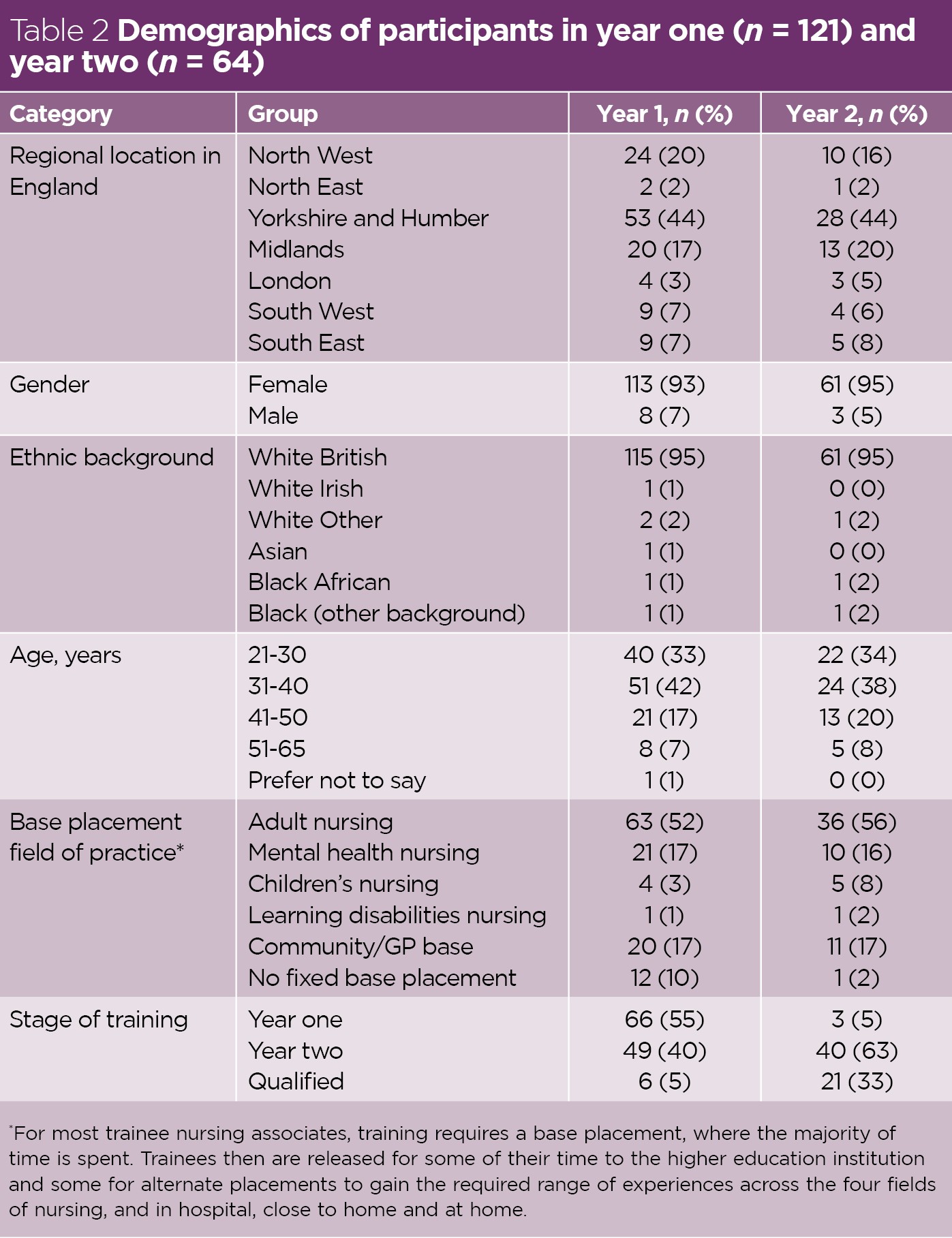

Of the recruited cohort (n = 151), 121 completed the survey in year one; 64 (53%) of these completed the survey in year two. Table 2 outlines the demographic data for those who completed the survey in year one and year two.

Despite the drop-off in year two, the location, gender, ethnic background, age distribution and the base placements remained similar across the two years, suggesting that this attrition was evenly spread across the cohort. In year one, only six (5%) participants were qualified nursing associates. As expected, given that the study followed this cohort over time, this figure had increased by year two; at that stage, 21 (33%) participants were qualified nursing associates and most of the rest were in their second year of study.

Support

Across both years, clinical supervisors were the main source of support, with academic tutors, trainee nursing associate peers, and relatives and friends also being important (Fig 1). Clinical supervisors became an even more important source of support in year two (92% versus 80% in year one), while the role of academic tutors (64% versus 50%), peer trainees (66% versus 42%) and social media (23% versus 16%) all decreased. Support from family and friends remained consistent across the two years (51% versus 50%).

In year one and year two, sources of support classified as ‘other’ included colleagues at base placement, clinical educators or practice facilitators, managers and work colleagues. Support from these sources increased by year two, as did support from other nursing associates (Fig 1).

Despite reporting having these sources of support, only 68 (56%) participants in year one felt that they were often or very often adequately supported in the clinical setting, and 19 (16%) felt they were never or rarely adequately supported. By year two, 41 (64%) felt they were often or very often adequately supported, and only seven (11%) felt they were never or rarely adequately supported.

Career plans

The responses on future career plans are shown in Fig 2. A lower percentage of participants were looking to return to work in their previous setting in year two (9%) compared with year one (17%). A higher proportion of participants wished to remain in their current workplace by year two (45%) compared with year one (34%). A similar percentage of participants at year one (32%) and year two (34%) had plans to move to a different clinical setting, either in their own organisation or in a different organisation.

Other career plans across year one and two included being undecided, becoming an RN and, in two cases (both year one), moving into a different career all together.

Becoming an RN

In terms of intentions to become an RN, there was little change between year one (52%) and year two (53%). There was a slightly lower percentage who were unsure about whether to become an RN in year two (36%) compared with year one (40%), and a slightly higher percentage who were not planning to become an RN in year two (11%) compared with year one (8%).

These slight differences overall do not mean individual trainees did not change their plans over time. For those who had said, in year one, that they did not plan to become an RN (n = 10) and who completed the year two survey (n = 8), one had changed their mind and another three were thinking about doing so. Conversely, by year two, three participants, who had stated in year one that they were thinking about RN training, said they were no longer doing so.

Discussion

A degree of support, or at least contact, in the clinical setting is anticipated as the majority of the trainee nursing associates were on the apprenticeship programme, which requires regular tripartite meetings between the trainee, employer and HE institution. Access to appropriate support has been shown to be important for promoting wellbeing and enhancing learning among trainee nursing associates (King et al, 2021; King et al, 2020; Coghill, 2018b).

The change in sources of support among our cohort – increase in support from clinical supervisors and nursing associates, and reduction in support from academic tutors, peer trainees and social media – might be linked to specific factors.

As clinical supervisors and trainee or newly qualified nursing associates become more familiar with this new role, then trust, understanding and skill in negotiating the supervisory relationship will likely increase. As Felton et al (2012) highlighted, these are necessary aspects for promoting confidence in nurses’ clinical supervisory relationships. This trust and understanding is enhanced by the increasing number of qualified nursing associates in the workplace, who can offer experience-based support to those in training.

Similar factors could account for the reported improvement in feeling supported in the clinical setting over the one-year study period. The gradual embedding of trainee and newly qualified nursing associates into clinical settings is leading some to report a greater understanding and acceptance of the role, and less role ambiguity (Lucas et al, 2021; Vanson and Bidey, 2019). This will improve the culture of support for these students and for staff.

During the Covid-19 crisis, the ability for trainee nursing associates to link with academic tutors and their trainee peers became more challenging (King et al, 2021), reducing opportunities for support from these sources. Yet, this does not explain the reduction in support from social media sources, which might have been expected to increase in the more-virtual Covid-19 environment. Understanding more about the nature of social media support for trainee nursing associates could form an interesting aspect of future research.

Similarly, the Covid-19 crisis itself, while proving challenging, also generated feelings of enhanced teamwork, cohesion and of making an important contribution among nursing associates and trainees (King et al, 2021); again, these are all facilitators and indicators of support.

Support needs may also be dependent on the base placement field of practice, stage of training or time since qualifying. For example, King et al (2021) showed higher levels of concern among trainee and qualified nursing associates in community settings compared with those in acute settings during the Covid-19 pandemic, which would require differing levels of support. These findings have implications for those working alongside nursing associates and trainees in clinical settings, who might provide support, for example, by sharing positive experiences of what they (ie, the nursing associate), can bring to the team.

A further finding in our study is the consistent support provided by relatives and friends – something that, as far as we are aware, has not been recognised in previous research. Future research could look at how and when different sources of support are provided to trainees as they progress through their training, and where there are gaps.

The policy underpinning the introduction of nursing associates rests, in part, on an assumption that approximately half would remain in that role and that half would become RNs (Council of Deans of Health, 2017). In practice, such plans become more complex, as workforce needs and personal career plans may not always align. Our findings show that only a very small percentage of respondents intended to remain as nursing associates. Just over half were definitely looking to transition to RN training and a further group (36-40%) remained undecided.

Workforce managers have shown themselves to be positive about the ability to ‘grow their own’ staff in terms of presenting career opportunities (particularly for HCAs) through the trainee nursing associate programme (Lucas et al, 2021; Kessler et al, 2020). However, there have also been concerns expressed about nursing associates not consolidating their new role before proceeding to nurse training. Lucas et al (2021) and Kessler et al (2020) have noted that organisations were keen to encourage nursing associates to “bed down” in their new role, some even using ‘golden handcuffs’ to keep staff for two years after qualifying. Given that many organisations had planned for specific numbers of nursing associates to fill the HCA/RN skills gap, this is predictable.

Lucas et al (2021) have also highlighted the importance that workforce managers place on nursing associate experience and knowledge already being embedded in the organisation; this is seen as an important aspect of ‘growing their own’.

It is encouraging that our findings show that the majority of participants intend to return to, or remain in, their current organisation. Around a third were looking to change the clinical setting in which they worked. This could be seen as a positive outcome of being exposed to a range of clinical settings during the generic, four-fields training; however, it could also be seen as disruptive to the organisation from a workforce solution perspective, as nursing associates move from clinical settings that had planned for their presence (Kessler et al, 2020).

It will be important to conduct more research and explore what influences the decision to transition among trainee and newly qualified nursing associates, and their decision to change clinical setting – particularly as our findings show that these can change for individuals as they progress through their nursing associate journey.

Limitations

Although this study has strength in its longitudinal design, there are also some limitations. As recruitment took place via HE institution partners (and social media), we did not have control over which trainees were contacted for the study and whether this represented all groups or just selected ones. Although some diversity was achieved in terms of geographical location, the majority of participants were in the North of England.

In addition, the group was almost all female, with a high number of White British participants, and over half were in adult nursing base placements. This has implications for the generalisability of our findings and implications for the areas on which future research might focus attention. Despite this, the limited diversity that was achieved was retained across the study year, suggesting that attrition was evenly spread across the participants’ characteristics.

As with all longitudinal cohort studies, not everyone who signed up continued to complete data over time. There was almost a 50% reduction in survey completion over the year of the study, limiting the opportunity to provide detailed statistical analysis. Nevertheless, the data presented provides, at minimum, an interesting picture of changes in support and career aspirations for trainee and newly qualified nursing associates, and the opportunity to consider the potential implications.

Collecting data by survey at two time points can only provide limited information on the issues considered here, so the findings must be approached with caution. However, as indicated earlier, this work is part of a larger programme of study that will seek to supplement the findings reported here with data from in-depth interviews with trainees and other stakeholders. As such, it forms one part of a larger body of research on trainee nursing associate motivations, experiences and aspirations.

Conclusion

It is clear that the support experiences and career aspirations of trainee nursing associates change over time, as the individuals gather experience across different clinical settings and the external context – most notably for this group, the Covid-19 crisis and the move into the qualified role – shifts. Support is gathered not only from formal sources, such as clinical supervisors, academic tutors and clinical educators, but also from clinical colleagues, peer nursing associates and trainees, and family and friends.

To help these new members of the nursing team achieve the best for patients, colleagues and themselves, we all have a part to play in generating a workplace culture that makes all staff feel valued, included and supported. Such a culture, which seeks to encourage and offer opportunities, will help build confidence in mastering clinical skills, including critical decision making.

It is important to understand trainee and newly qualified nursing associates’ career aspirations, and the motivations behind these – not only to support continuing professional development, but also for workforce planning. Understanding these aspirations and motivations can help align the organisational workforce need with personal career ambitions in ways that boost job satisfaction and feelings of organisational collegiality; this, in turn, helps with retention and recruitment.

Funding mechanisms for transitioning to RN training should be sustained for the healthcare system to benefit from a skilled and competent cohort of nursing associates wishing to take the next step.

Key points

- Different sources of support are used by trainee nursing associates as they progress through their training, and it is important to consider where gaps may occur

- Taking time to understand and share the positive aspects of the nursing associate role can help reduce concerns about the role and create a more supportive environment

- It is important to understand career motivations and aspirations at all stages of the nursing associate journey

- How aspirations and motivations align with the needs of clinical areas, the organisation and the wider healthcare system should be considered

● The project was funded by the Royal College of Nursing (RCN) as part of the Strategic Research Alliance between the RCN and the University of Sheffield. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the RCN or University of Sheffield.

Anderson M et al (2021) Securing a sustainable and fit-for-purpose UK health and care workforce. The Lancet; 397: 10288, 1992-2011.

Coghill E (2018a) An evaluation of how trainee nursing associates (TNAs) balance being a ‘worker’ and a ‘learner’ in clinical practice: an early experience study. Part 1/2. British Journal of Healthcare Assistants; 12: 6, 280-286.

Coghill E (2018b) An evaluation of how trainee nursing associates (TNAs) balance being a ‘worker’ and a ‘learner’ in clinical practice: an early experience study. Part 2/2. British Journal of Healthcare Assistants; 12: 7, 356-359.

Council of Deans of Health (2017) Nursing Associate Policy Update. London: CDH.

Davey M (2019) My trainee nursing associate journey. British Journal of Healthcare Assistants; 13: 3, 131-133.

Felton A et al (2012) Exposing the tensions of implementing supervision in pre-registration nurse education. Nurse Education in Practice; 12: 1, 36-40.

Glasper A (2018) Registration of nursing associates gains government backing. British Journal of Healthcare Assistants; 12: 7, 333-335.

Health Education England (2015) Raising the Bar. Shape of Caring: A Review of the Future Education and Training of Registered Nurses and Care Assistants. HEE.

Kessler I et al (2020) Evaluating the Introduction of the Nursing Associate Role in Health and Social Care: Interim Report. London: NIHR Policy Research Unit in Health and Social Care Workforce, The Policy Institute, King’s College London.

King R et al (2021) The impact of Covid-19 on the work, training and well-being experiences of nursing associates in England: a cross-sectional survey. Nursing Open; doi: 10.1002/nop2.928 (early online).

King R et al (2020) Motivations, experiences and aspirations of trainee nursing associates in England: a qualitative study. BMC Health Services Research; 20: 802.

The King’s Fund (2018) The Health Care Workforce in England: Make or Break? London: TKF.

Lucas G et al (2021) Healthcare professionals’ views of a new second-level nursing associate role: a qualitative study exploring early implementation in an acute setting. Journal of Clinical Nursing; 30: 9-10, 1312-1324.

Marć M et al (2019) A nursing shortage: a prospect of global and local policies. International Nursing Review; 66: 1, 9-16.

Nursing and Midwifery Council (2018) Standards of Proficiency for Nursing Associates. NMC.

Vanson T, Beckett A (2018) Evaluation of Introduction of Nursing Associates: phase 1 report for Health Education England. Traverse.

Vanson T, Bidey T (2019) Introduction of Nursing Associates: Year 2 Evaluation Report. Traverse.

Nursing Times Resources for the nursing profession

Nursing Times Resources for the nursing profession

Have your say

or a new account to join the discussion.